Training a Deep Q-Network to Master Uno: A Comprehensive Study in Reinforcement Learning for Imperfect Information Games

Training a Deep Q-Network to Master Uno: A Comprehensive Study in Reinforcement Learning for Imperfect Information Games

Mohammed Alshehri — mohammed@redec.io

Abstract

We study Deep Q-Network (DQN) learning for Uno, an imperfect-information card game with stochastic transitions and a variable legal action set. We introduce a fixed-dimensional state encoding and a masked discrete action encoding, and train the agent using tournament-based experience collection.

Using 100,000 random-play simulations, we report baseline game statistics and evaluate the learned agent against API-served LLM opponents. Because LLM endpoints may change over time, these results are conditional on the specific model identifiers and access configuration.

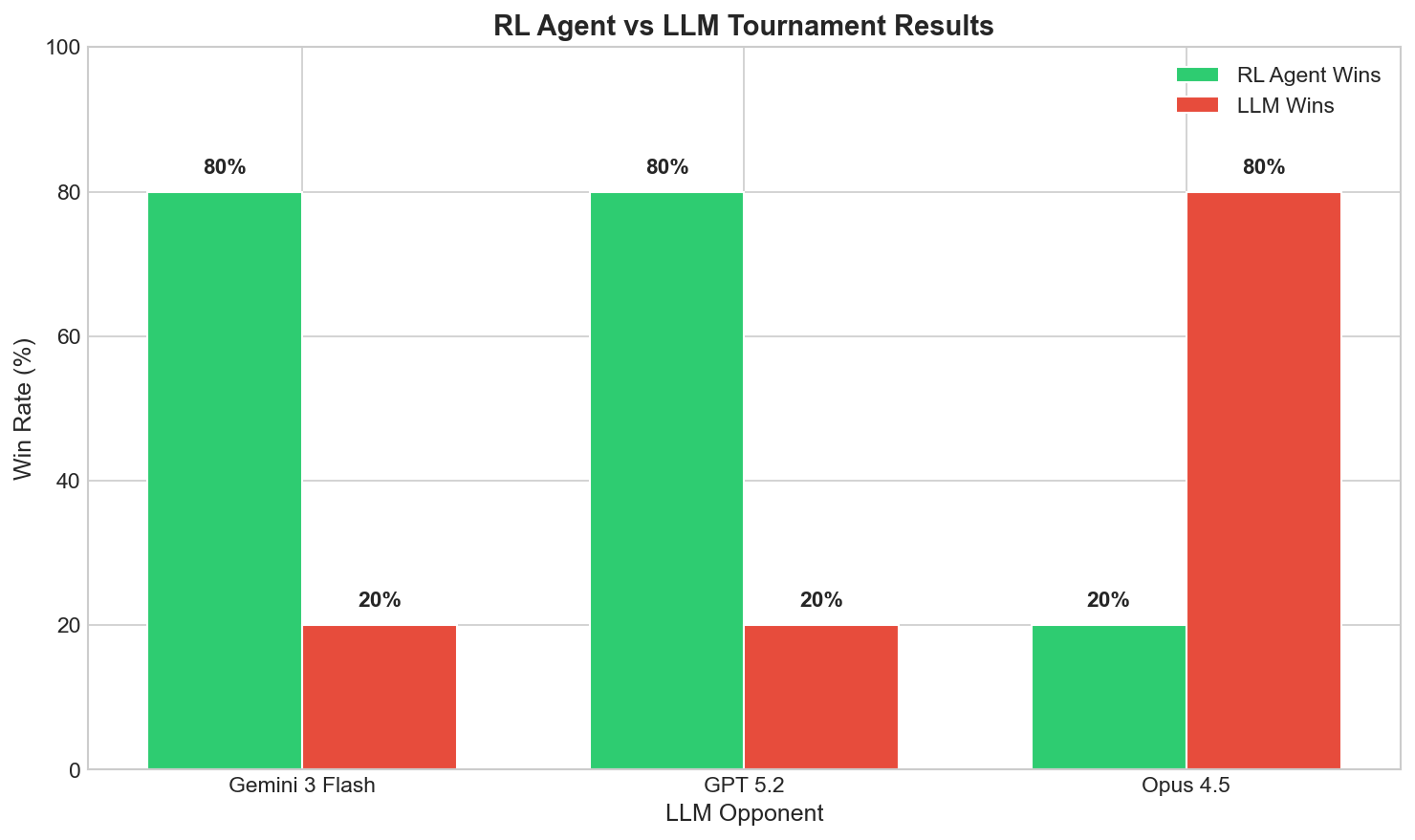

Principal finding: Our DQN agent achieves an 80% win rate against Gemini 3 Flash and GPT 5.2 in our evaluation harness, but only a 20% win rate against Opus 4.5.

Keywords: reinforcement learning; DQN; imperfect information; card games; evaluation; large language models

Introduction and Motivation

The challenge of imperfect information games

Card games are a standard benchmark for decision-making under uncertainty. Unlike perfect-information games (e.g., Chess, Go), Uno introduces:

This work builds on deep reinforcement learning methods for control (Mnih et al. 2015) and subsequent improvements in stabilizing value-based learning (Hasselt et al. 2016).

Imperfect information: opponents’ hands are hidden.

Stochastic transitions: shuffling and drawing induce randomness.

Variable action spaces: legal actions change with the top discard card and the hand.

Delayed rewards: local actions may have long-term consequences.

Research objectives

We pursue four objectives:

Statistical characterization of baseline play.

Implementation and training of a DQN agent.

Comparative evaluation against random baselines and frontier LLMs.

Deployment of an interactive web interface for demonstration.

Contributions

Our contributions include (i) a fixed-dimensional state encoding, (ii) tournament-based experience collection, (iii) empirical comparisons versus LLM-based opponents, and (iv) a deployable system design.

Problem setting and rules

Two-player Uno variant

We study a two-player version of Uno. The game is played with a standard Uno deck and proceeds in alternating turns until one player plays their final card. Special action cards modify turn order or force draws; wild cards allow the acting player to declare the next active color. For baseline rule definitions we follow the official Uno instructions (Mattel n.d.). Implementation note: Uno has rule variants (e.g., stacking draw cards); therefore, any empirical results in this paper should be interpreted with respect to the specific rules implemented in our codebase (mohammed840 2026).

Learning problem formulation

We model the environment as a partially observable sequential decision problem: the agent observes its private hand and public information (e.g., discard top card) but not the opponent’s hand (Kaelbling et al. 1998). We train the agent using episodic win/loss feedback as the primary learning signal.

Related work

Deep reinforcement learning for control with value-based methods has been widely studied, including the original DQN formulation (Mnih et al. 2015) and Double DQN (Hasselt et al. 2016). Multiple stabilisation and performance extensions have been proposed, including dueling networks (Wang et al. 2016), prioritised experience replay (Schaul et al. 2016), and combined variants such as Rainbow (Hessel et al. 2018). For card-game research and benchmarking, RLCard provides a general-purpose toolkit (Zha et al. 2019).

A course report by Brown, Jasson and Swarnakar (Brown et al. 2020) also explores Uno with DQN and DeepSARSA in an RLCard-based environment, focusing on multi-player games (3–5 players) and tournament-style experience collection.

Game Statistics from Large-Scale Simulations

Experimental setup

We simulated 100,000 games under uniformly random legal play. For each episode we recorded total turns to termination, the starting player, and per-player counts of cards played and drawn. Our implementation is compatible with standard card-game RL toolkits (Zha et al. 2019).

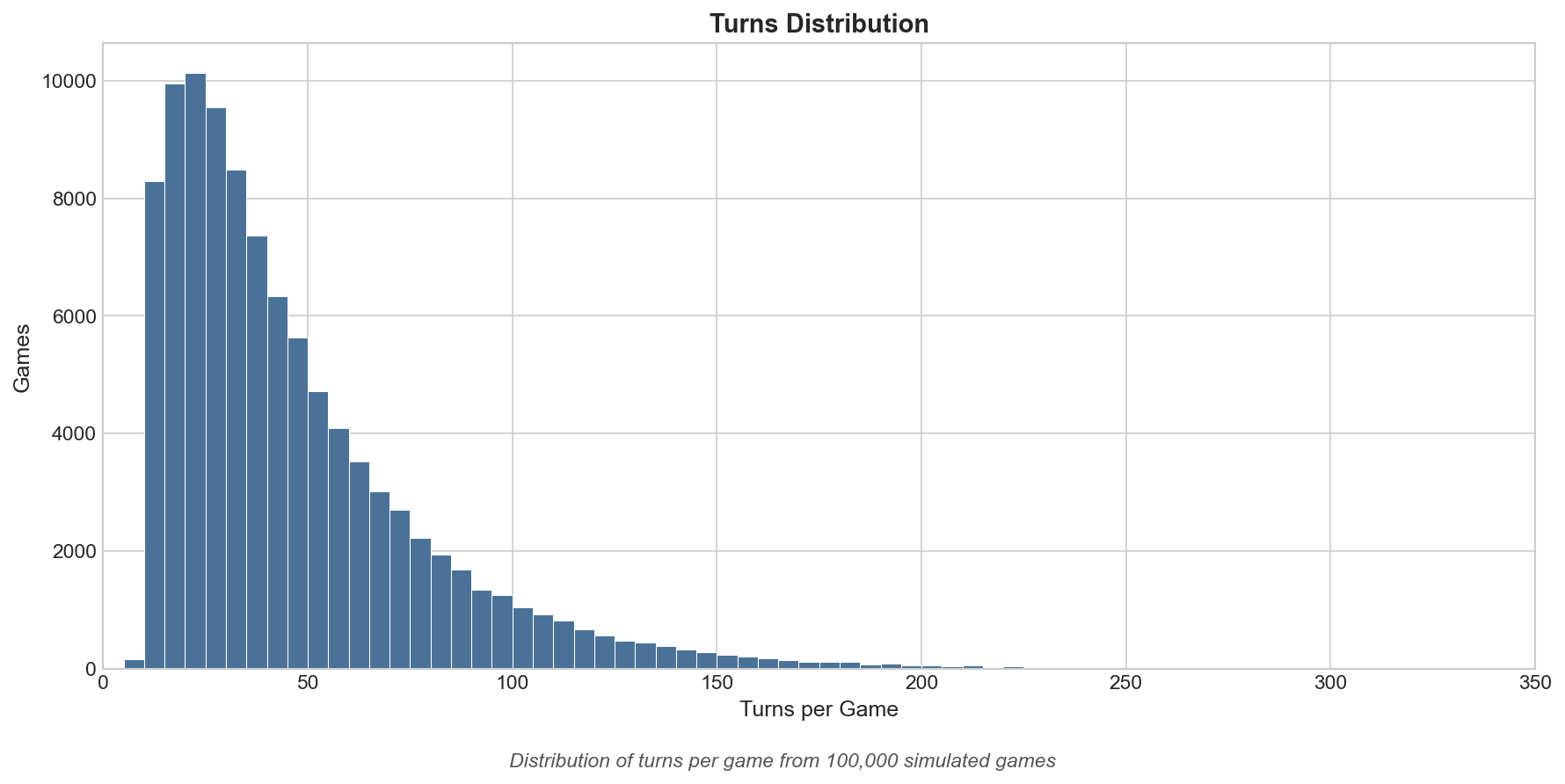

Game length distribution

Figure 1 visualizes the empirical episode-length distribution used to calibrate training horizons. The pronounced right tail indicates that while many games finish quickly, a non-negligible fraction of episodes are substantially longer, which motivates reporting both central tendency and tail statistics.

Summary statistics (random baseline):

| Statistic | Value |

|---|---|

| Mean | 46.5 turns |

| Median | 37.0 turns |

| Mode | 13 turns |

| Standard deviation | 33.8 turns |

| Minimum | 7 turns |

| Maximum | 418 turns |

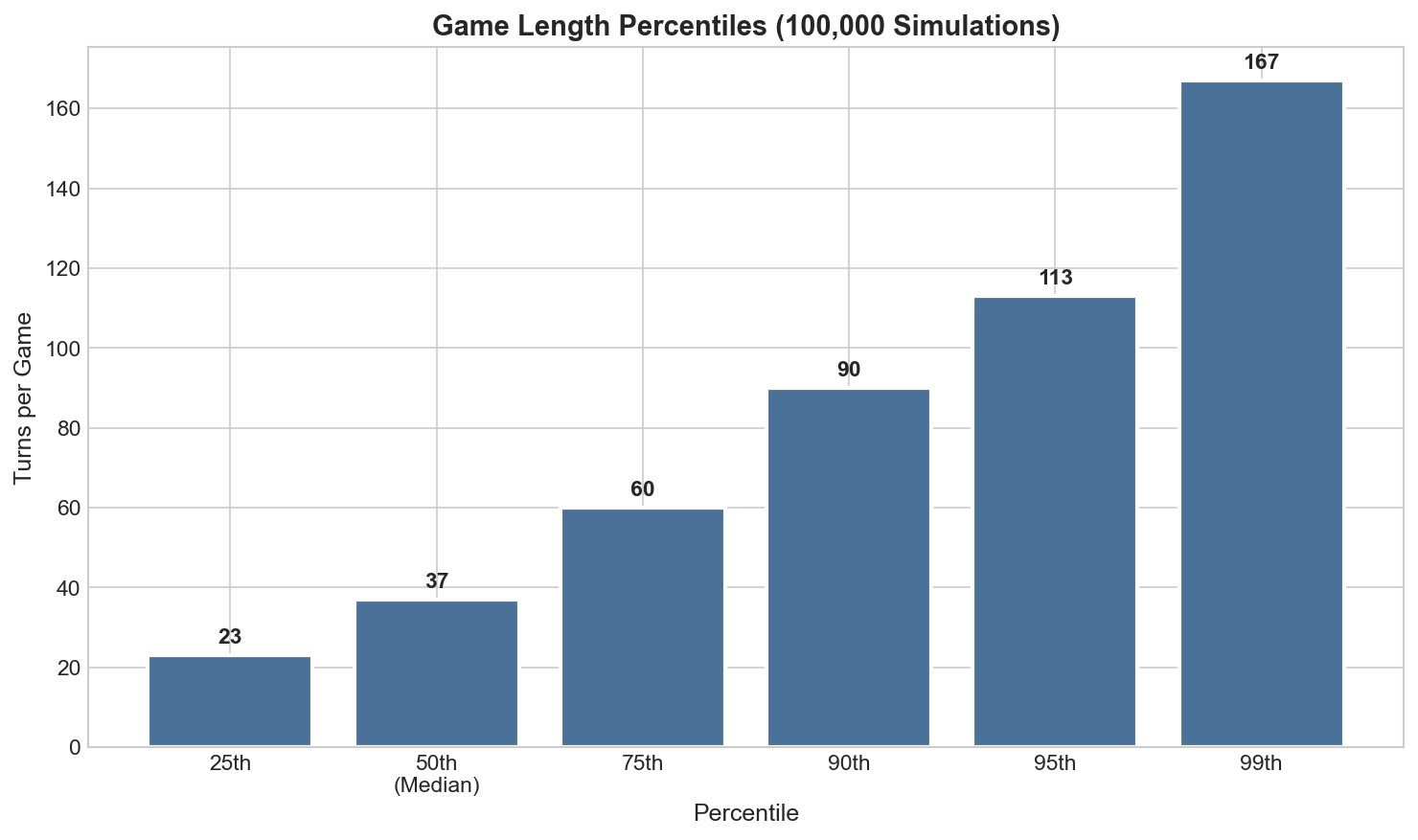

Percentile analysis

Figure 2 complements the histogram by summarizing the episode-length distribution at selected quantiles, which is often more stable than single-point summaries such as the mean.

| Percentile | Turns | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 25th | 23 | 25% of games complete by this point |

| 50th (median) | 37 | Half of games complete |

| 75th | 60 | Three quarters of games complete |

| 90th | 90 | Only 10% exceed this length |

| 95th | 113 | Long games (5% tail) |

| 99th | 167 | Extreme tail (1%) |

These percentiles informed our choice of discount factor \(\gamma=0.95\), which appropriately weights future rewards across typical game horizons.

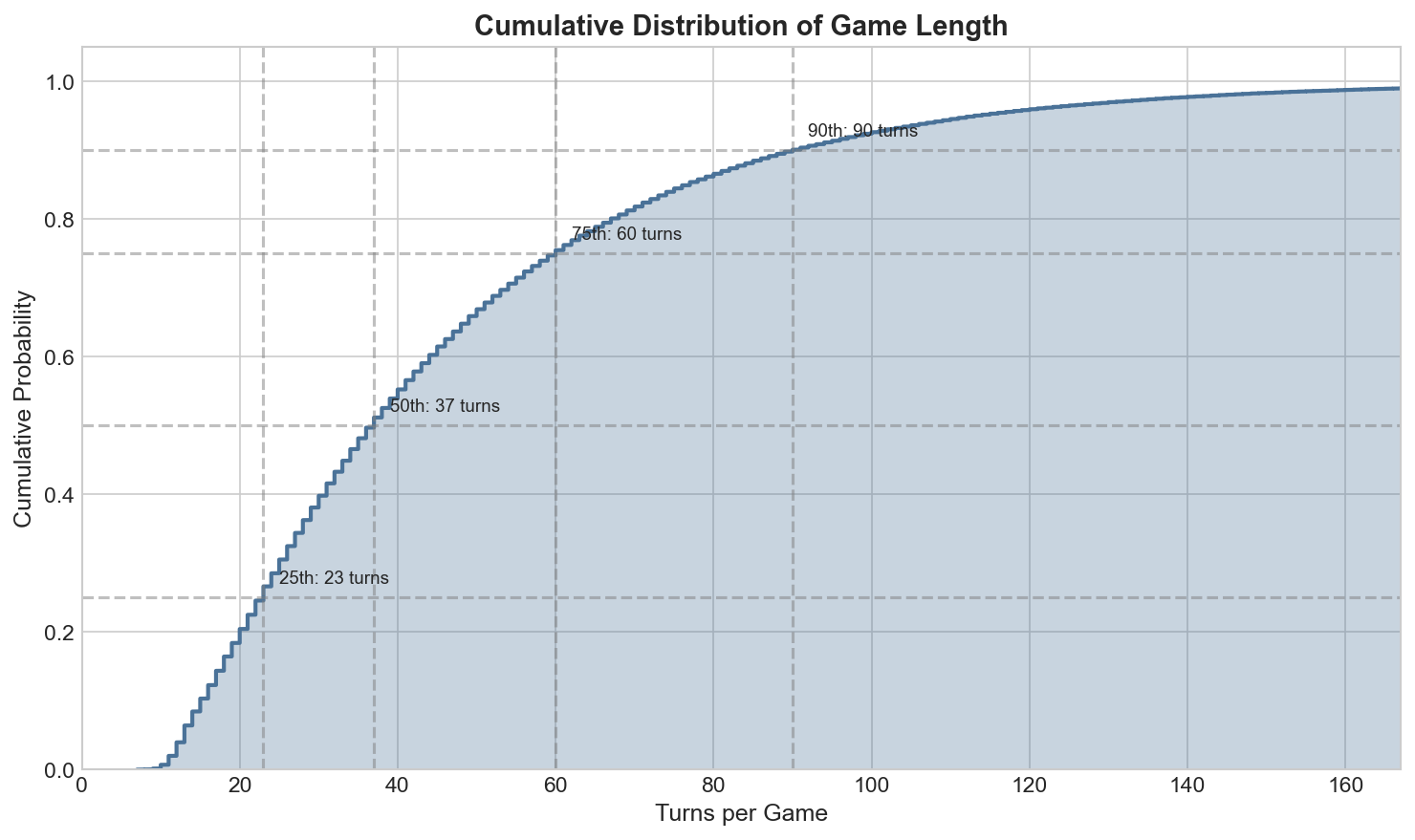

Cumulative distribution function

Figure 3 provides a cumulative view of episode length; for example, the value at \(x\) turns corresponds to the fraction of games that terminate within \(x\) turns.

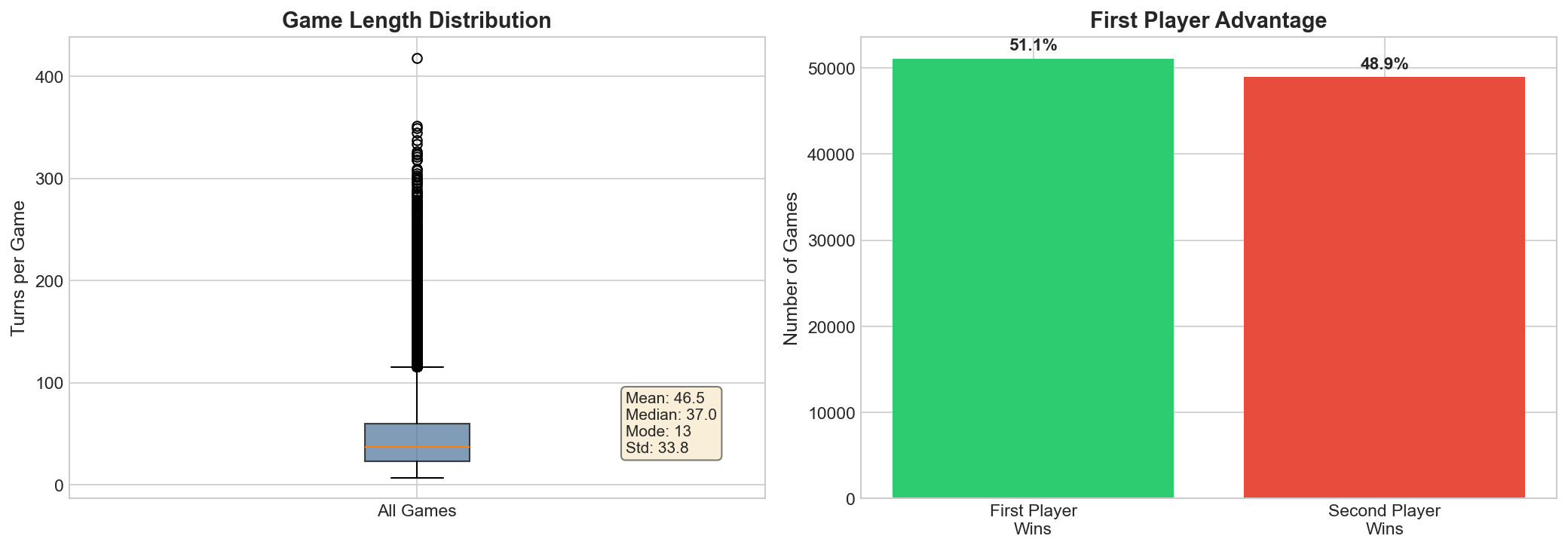

First-player advantage

Figure 4 summarizes variability in episode length and reports the estimated advantage of moving first under random play, which serves as a basic sanity check for the simulator and a reference point for learned agents.

We observe a modest first-player advantage: first player wins 51.07% of games (51,068 / 100,000).

Deep Q-Network (DQN) Architecture

Overview and design rationale

Deep Q-Networks (DQN) learn a parametric approximation \(Q(s,a;\theta)\) to the optimal action-value function and are well suited to environments with (i) large or continuous observation spaces and (ii) discrete actions (Mnih et al. 2015). In our setting, the observation is a fixed-length 420-dimensional feature vector (Section 5), while the action set is a 61-way discrete encoding with dynamic legality constraints (Section 6).

Two practical challenges are central in Uno: (a) stochasticity and partial observability (hidden opponent hand and random draws), and (b) variable legal actions. To address (b), we explicitly apply an action mask at decision time so that the policy never selects illegal actions.

Theoretical foundation

DQN builds on the Bellman optimality equation for Markov decision processes: \[\begin{equation} Q^*(s,a)=\mathbb{E}\left[r_{t+1}+\gamma \max_{a'} Q^*(s_{t+1},a')\mid s_t=s, a_t=a\right]. \end{equation}\]

Given a transition tuple \((s_t,a_t,r_{t+1},s_{t+1})\), the one-step TD target used by DQN is \[\begin{equation} y_t \;=\; r_{t+1} + \gamma\max_{a'} Q\bigl(s_{t+1},a';\theta^{-}\bigr), \end{equation}\] where \(\theta^{-}\) denotes parameters of a slowly-updated target network that stabilises learning (Mnih et al. 2015).

We minimise the squared TD error over samples drawn from a replay buffer: \[\begin{equation} \mathcal{L}(\theta)=\mathbb{E}_{(s,a,r,s')\sim\mathcal{D}}\left[\left(y - Q(s,a;\theta)\right)^2\right]. \end{equation}\]

Double DQN target (reduced overestimation).

In standard DQN, the maximisation in \(y_t\) can introduce positive bias (“overestimation”). We therefore use the Double DQN decomposition, selecting the greedy action under the online network but evaluating it with the target network (Hasselt et al. 2016): \[\begin{equation} y_t^{\mathrm{DDQN}} \;=\; r_{t+1} + \gamma\,Q\Bigl(s_{t+1},\arg\max_{a'}Q(s_{t+1},a';\theta);\theta^{-}\Bigr). \end{equation}\]

Experience replay and target network

DQN uses two key stabilisation mechanisms (Mnih et al. 2015):

Experience replay. Transitions are stored in a replay buffer \(\mathcal{D}\) and mini-batches are sampled uniformly during training. This breaks short-term temporal correlations and improves sample efficiency.

Target network. A separate network with parameters \(\theta^{-}\) is updated periodically (every \(C\) gradient steps) from the online network parameters \(\theta\), reducing non-stationarity of TD targets.

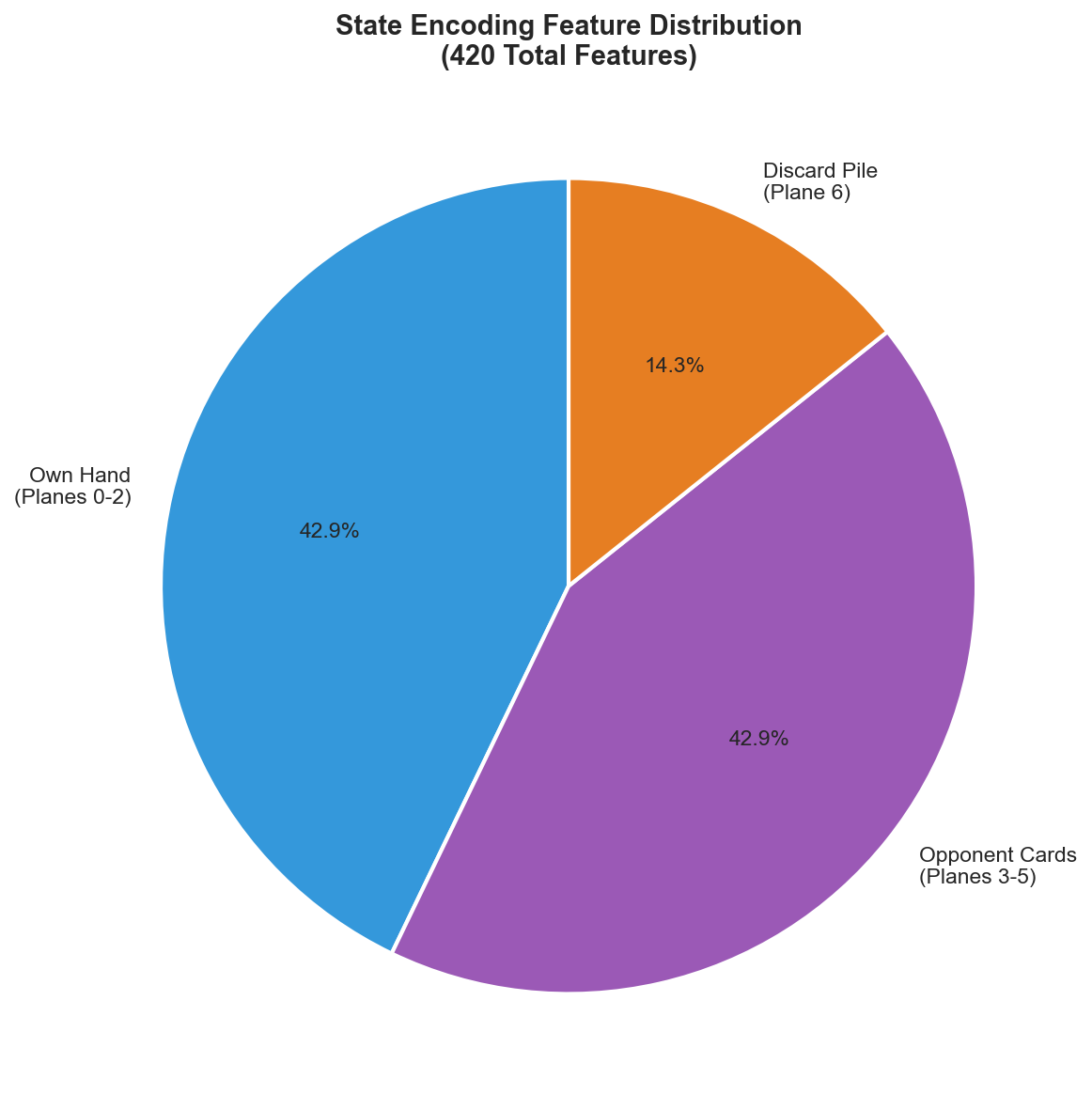

State representation

We encode the game state as a 420-dimensional feature vector structured as 7 planes of 60 features each (4 colors \(\times\) 15 card types). This representation is designed to be (i) fixed-dimensional, (ii) permutation-invariant with respect to hand order, and (iii) directly aligned with Uno’s public and private information.

Detailed encoding scheme:

| Planes | Features | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 0–2 | 180 | Own hand card-count buckets (0, 1, 2+ copies) |

| 3–5 | 180 | Estimated opponent card counts (0, 1, 2+) |

| 6 | 60 | Current discard pile top card (one-hot) |

| Total | 420 | Complete state representation |

Why bucketed counts?

We use \((0,1,2+)\) buckets rather than raw counts to keep the input scale bounded and to emphasise strategically relevant distinctions (e.g., “have at least one playable card type” versus “none”). In a two-player setting, a coarse opponent model (estimated counts) is often sufficient to induce defensive play (e.g., holding wild cards) without requiring full belief-state inference.

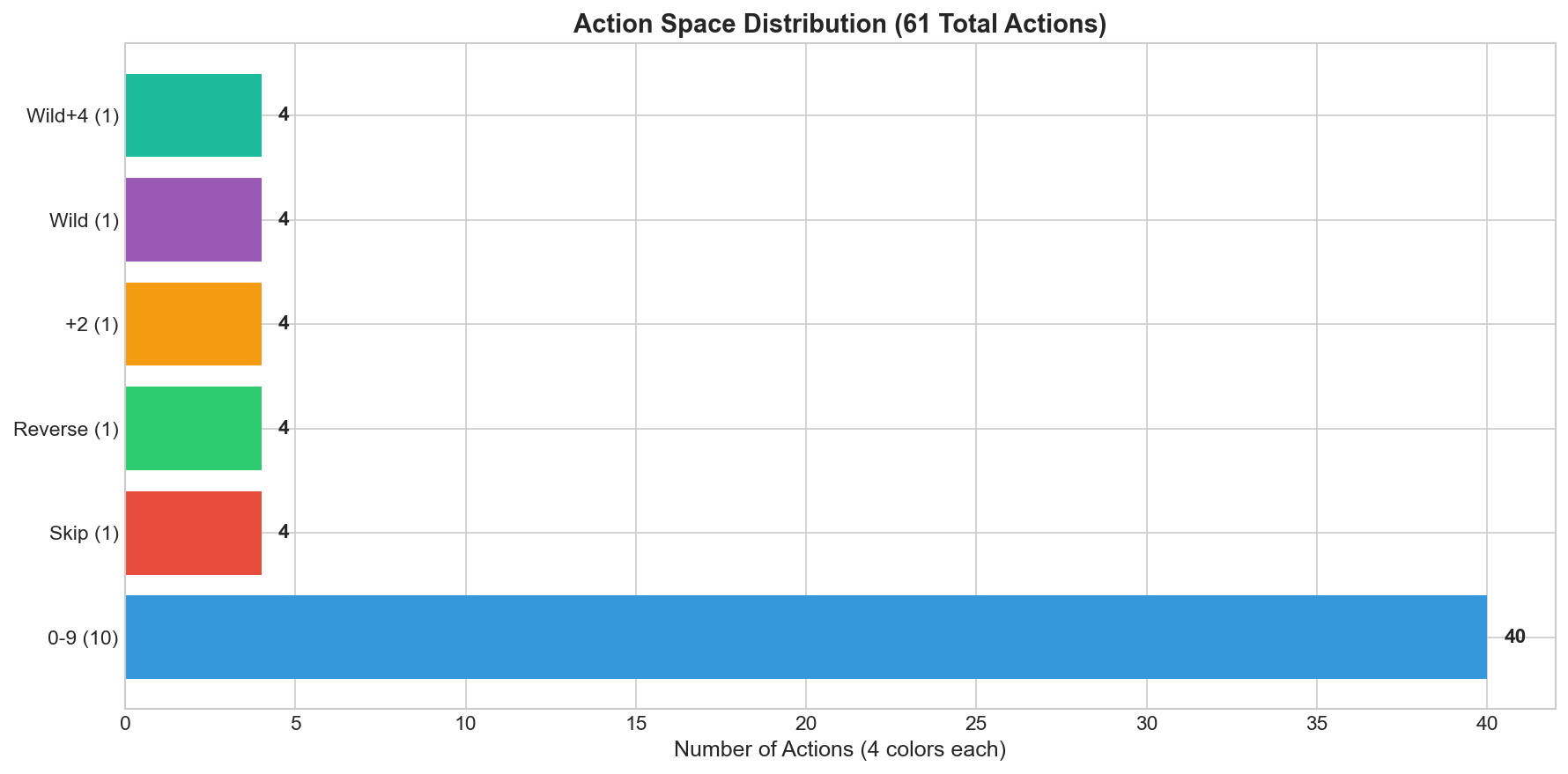

Action space and legality masking

The action space consists of 61 discrete actions representing all possible moves; illegal actions are masked during action selection.

| Action range | Count | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 0–39 | 40 | Number cards (0–9 \(\times\) 4 colors) |

| 40–43 | 4 | Skip (4 colors) |

| 44–47 | 4 | Reverse (4 colors) |

| 48–51 | 4 | Draw Two (4 colors) |

| 52–55 | 4 | Wild (declare 4 colors) |

| 56–59 | 4 | Wild Draw Four (declare 4 colors) |

| 60 | 1 | Draw from deck |

Let \(m(s)\in\{0,1\}^{61}\) be a binary mask indicating action legality in state \(s\). During greedy action selection we compute \[\begin{equation} a^* \;=\; \arg\max_{a}\; \Bigl(Q(s,a;\theta) + (1-m_a(s))\cdot (-\infty)\Bigr), \end{equation}\] which guarantees that illegal moves are never chosen.

Network architecture

Our Q-network maps 420 input features to 61 Q-values using a fully-connected multilayer perceptron. This choice is appropriate because the observation is already a compact, hand-crafted vector rather than an image.

Regularisation and optimisation details.

Dropout provides mild regularisation against overfitting to early replay-buffer distributions. In addition, common DQN stabilisation practices include gradient clipping and the use of a robust loss (Huber) (Mnih et al. 2015). (We report the MSE objective above for clarity; in practice, replacing MSE with Huber is a drop-in change.)

Relation to common DQN extensions (context)

Several extensions to DQN can further improve stability and performance, including dueling networks (Wang et al. 2016), prioritised experience replay (Schaul et al. 2016), and combined “Rainbow” variants (Hessel et al. 2018). We retain a relatively simple architecture to keep the Uno pipeline reproducible, and focus our improvements on state encoding, action masking, and tournament-style experience collection.

Training Methodology

Tournament-based experience collection

Each training iteration aggregates experience over a tournament of \(N\) complete games, improving stability and diversifying trajectories.

Experiments and reproducibility

Experimental protocol

All experimental results in this paper are conditional on the ruleset and experimental protocol implemented in the accompanying codebase (mohammed840 2026). In our implementation, training uses fixed random-policy opponents in a two-player setting (the learning agent is always player 0), and the reward is terminal only (\(+1\) for win, \(-1\) for loss, \(0\) otherwise).

Metrics and reporting

We report (i) win rate and average reward for tournament-style evaluation, and (ii) summary statistics of game length (turns per game) under random play. The code writes training metrics to runs/<run_id>/metrics_train.csv and evaluation metrics to runs/<run_id>/metrics_eval.csv (mohammed840 2026).

Reproducibility checklist

Random seeds. Training and evaluation set seeds for NumPy and PyTorch; the environment is also initialised with a seed parameter (mohammed840 2026).

Artifacts. Each run stores

config.json, per-iteration tournament logs (tournaments/dqn_iter_<i>.jsonl), and plots underruns/<run_id>/plots/(mohammed840 2026).LLM evaluation. OpenRouter opponents are specified by model slugs (e.g.,

google/gemini-3-flash-preview,openai/gpt-5.2,anthropic/claude-opus-4.5) and queried withmax_tokens=50andtemperature=0.1in our adapter (mohammed840 2026).

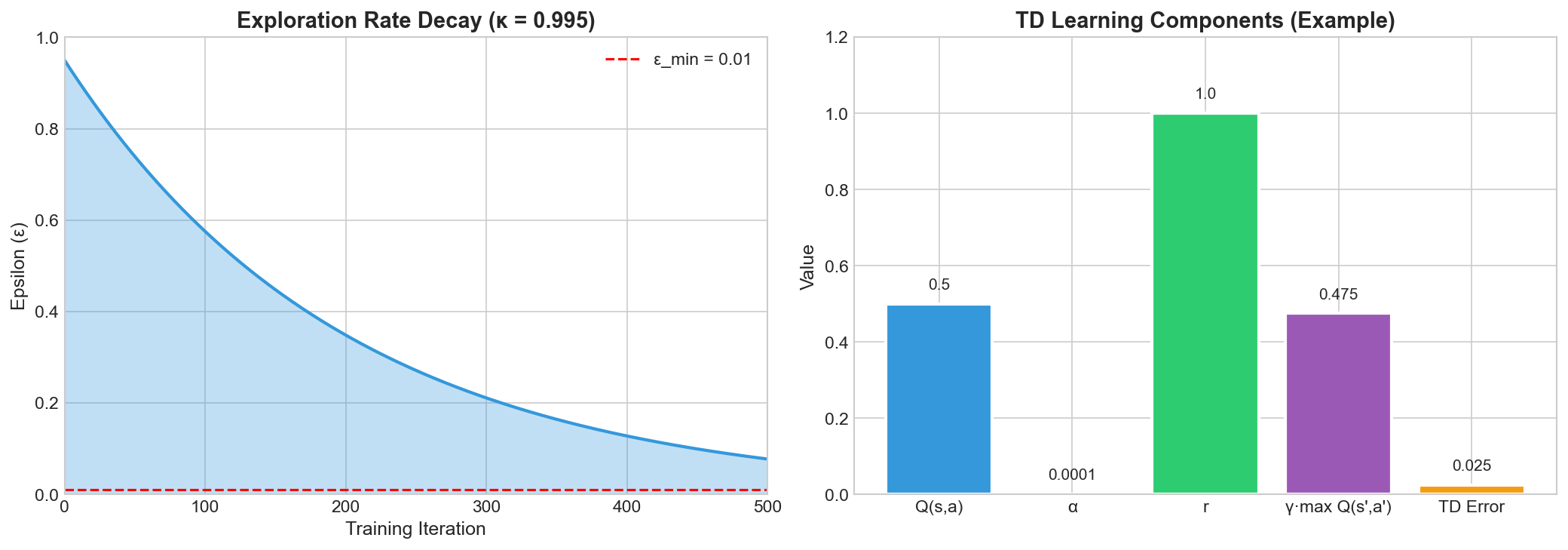

Hyperparameter configuration

Figure 7 summarizes key training signals, in particular the exploration schedule that transitions from broad exploration to more exploitative play as the replay buffer grows.

| Hyperparameter | Value | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Learning rate (\(\alpha\)) | \(10^{-4}\) | Stable learning without oscillation |

| Discount factor (\(\gamma\)) | 0.95 | Appropriate for \(\sim\)40-turn games |

| Initial epsilon (\(\varepsilon_0\)) | 0.95 | High initial exploration |

| Epsilon decay (\(\kappa\)) | 0.995 | Gradual transition to exploitation |

| Minimum epsilon (\(\varepsilon_{\min}\)) | 0.01 | Maintain exploration |

| Batch size | 256 | Efficient GPU utilization |

| Replay buffer size | 100,000 | Experience diversity |

| Target update frequency | 100 | Stabilize TD targets |

| Games per iteration | 100 | Tournament size |

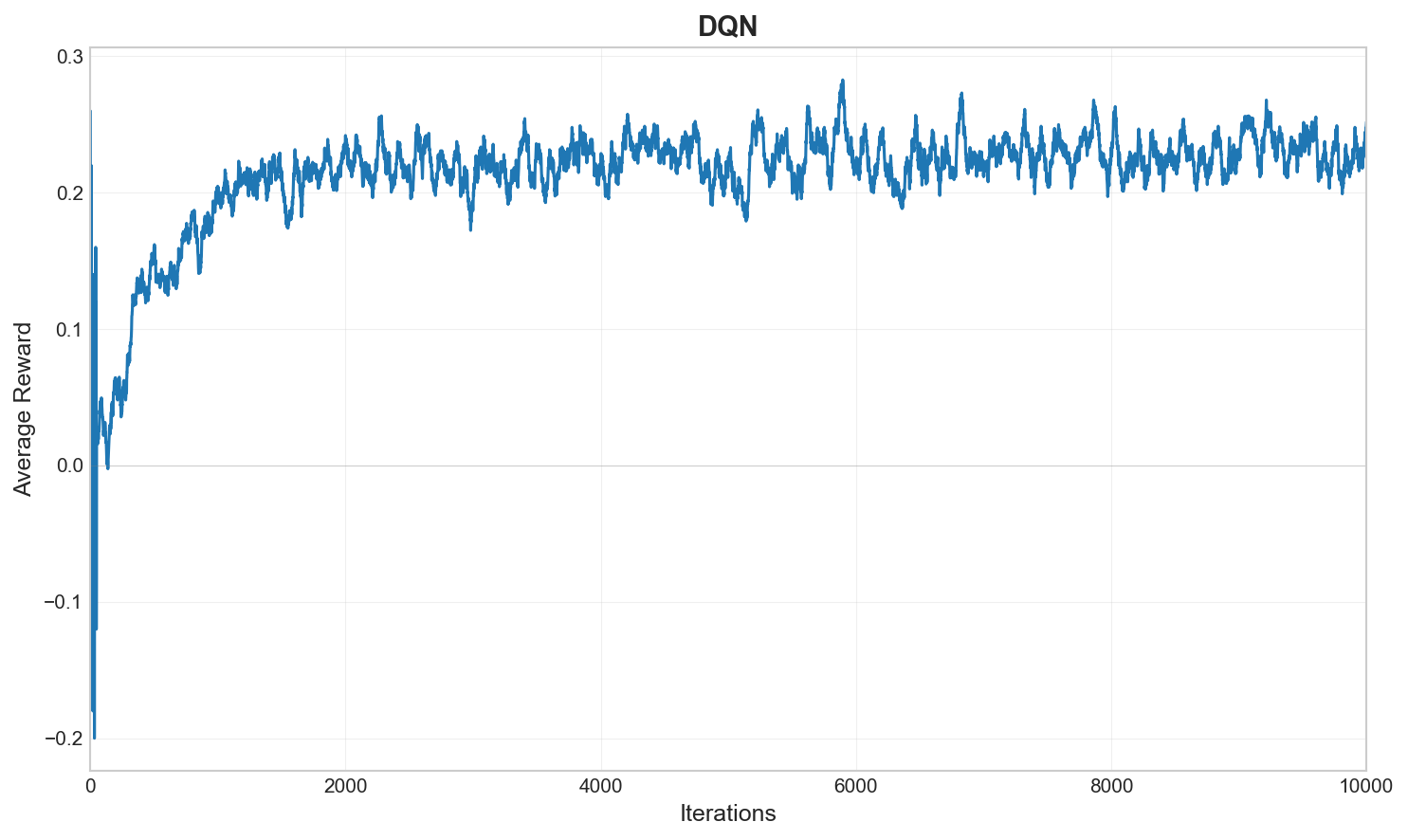

Training dynamics

Figure 8 reports the evolution of training reward, which serves as a coarse indicator of policy improvement and training stability over iterations.

The training progression exhibits three phases: (i) rapid learning in early iterations (1–50), (ii) strategy refinement (50–200), and (iii) convergence after approximately 200 iterations.

Evaluation: RL Agent vs. Large Language Models

Experimental design

We evaluate the trained agent in head-to-head tournaments against multiple LLM opponents accessed via an API, focusing on win-rate as the primary metric.

Protocol.

For each opponent configuration, we run 100 games (consistent with the win/loss counts reported in Table 1). In our evaluation harness, the learning agent is player 0 and the starting player is determined by the environment reset; we do not explicitly force alternation of the starting player. The LLM opponents are accessed through an external API gateway; in our implementation we use OpenRouter (OpenRouter n.d.). We use the OpenRouter model identifiers google/gemini-3-flash-preview, openai/gpt-5.2, and anthropic/claude-opus-4.5, queried with temperature=0.1 and max_tokens=50 (mohammed840 2026).

Tournament results

Figure 9 provides a compact summary of the main comparative evaluation, indicating which LLM-based opponents are consistently outperformed by the learned policy and highlighting cases where the LLM exhibits a systematic advantage.

| Opponent | RL wins | LLM wins | RL win rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gemini 3 Flash | 80 | 20 | 80% |

| GPT 5.2 | 80 | 20 | 80% |

| Opus 4.5 | 20 | 80 | 20% |

Qualitative analysis of LLM behavior

Careful observation of gameplay revealed systematic differences in decision-making.

Gemini 3 Flash and GPT 5.2

In qualitative inspection of gameplay, these models often selected immediately playable cards without clear evidence of longer-horizon hand management. This observation is anecdotal and may be sensitive to the prompt template and sampling configuration (mohammed840 2026).

Opus 4.5

In contrast, Opus 4.5 displayed behaviors consistent with longer-horizon tactics, including deliberate hand management (preserving wild cards for flexibility), proactive color control (shifting to colors held in greater quantity), occasional defensive play (drawing instead of playing the last matching card), and actions consistent with anticipating inferred opponent constraints.

Interpretation: hypothesis on longer-horizon decision making

We hypothesize that the observed advantage of Opus 4.5 in our setting may reflect differences in longer-horizon decision making (e.g., preserving flexibility, controlling colors, or implicitly tracking opponent constraints). This interpretation is qualitative and requires further controlled study; in particular, it would benefit from (i) an explicitly specified prompt and sampling configuration for the LLM opponent, and (ii) quantitative ablations that isolate which information and planning components contribute to performance.

Discussion and Future Work

Summary of findings

Overall, we find that DQN is viable for Uno in the sense that the agent learns competitive strategies without hand-crafted rules. We also find that performance varies substantially across LLM-based opponents under our evaluation protocol, so opponent choice strongly affects observed win rates. The large-scale simulation analysis provides practical guidance for selecting design choices such as discounting and evaluation horizons, while the LLM results highlight the importance of careful reproducibility reporting for API-served models.

Limitations

LLM evaluations are API-dependent and therefore difficult to reproduce at scale. In addition, we restrict attention to a two-player variant (excluding multi-player dynamics), and self-play training may reduce robustness to diverse opponent policies.

Future work

Promising directions include integrating explicit planning (e.g., Monte Carlo tree search) with learned value functions, population-based training against diverse opponents, extension to multi-agent (3–4 player) settings, and improved opponent modeling. Related advances in policy optimization and self-play motivate these directions (Schulman et al. 2017; Silver et al. 2017).

Conclusion

We presented a complete pipeline for training, evaluating, and deploying a DQN agent for Uno. Our systematic approach—from 100,000-game statistical analysis through tournament-based training to LLM tournament evaluation—yields practical artifacts and insights.

We observe large differences in win rates across the evaluated LLM opponents under our protocol. Because LLM evaluation is API-dependent and model endpoints may change over time, these results should be interpreted as conditional on the exact access configuration, and they motivate further controlled experiments and hybrid approaches that combine reinforcement learning with planning.

Reproducibility (Commands)

Environment setup

Source code and instructions are available in the accompanying repository (mohammed840 2026).

# Clone repository

git clone https://github.com/mohammed840/policy-uno.git

cd policy-uno

# Install dependencies

pip install -e .

# Set API key for LLM evaluation (optional)

export OPENROUTER_API_KEY=your_key_hereTraining and evaluation commands

# Run game statistics simulation (random baseline)

python -m rl.game_statistics --games 100000 --seed 42

# Train DQN

python -m rl.dqn_train --iters 1000 --games_per_iter 100 --seed 42

# Evaluate a saved run

python -m rl.eval --run_id <run_id> --games 1000 --seed 42

# Generate plots for a run

python -m rl.plots --run_id <run_id>Web server

# Start the web application

python3 web/server.py

# Access at http://localhost:5000